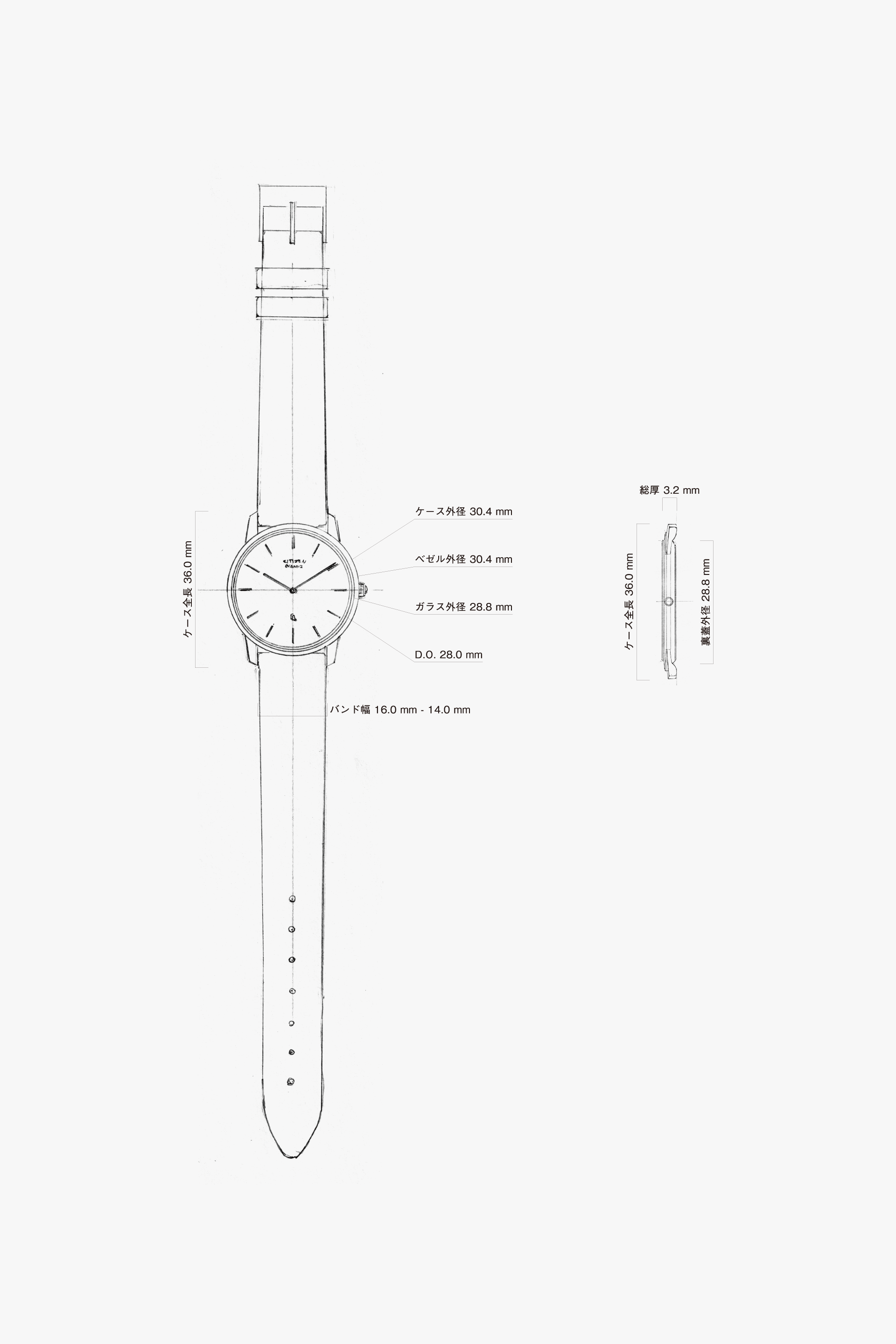

As a form that further accentuates the watch equipped with the world’s thinnest analog quartz movement at the time, meticulous treatments and design processes that make the watch appear even thinner—many of which are too fine to be recognized by the naked eye—have been applied throughout. This is a subtractive design that does not compromise thinness.

The height of the fitting between the glass and the bezel has been minimized, and the glass itself is as thin as possible. On both sides of the applied index, which has a protruding cross-section, there are extremely fine cuts that are indistinguishable to the naked eye. Additionally, the case is designed to make the side surface as thin as possible, and by aligning the outside diameter of the bezel and the case, the number of ridges forming the exterior is kept to a minimum. Each of these is a very fine design detail, but together, these small refinements create a sense of precision in the watch’s appearance.

Through the accumulation of such minute details—so fine they cannot be distinguished without a magnifying glass—and calculated minimal design treatments, the form expresses the ultimate thinness.

A minimal design with elements pared down as much as possible.

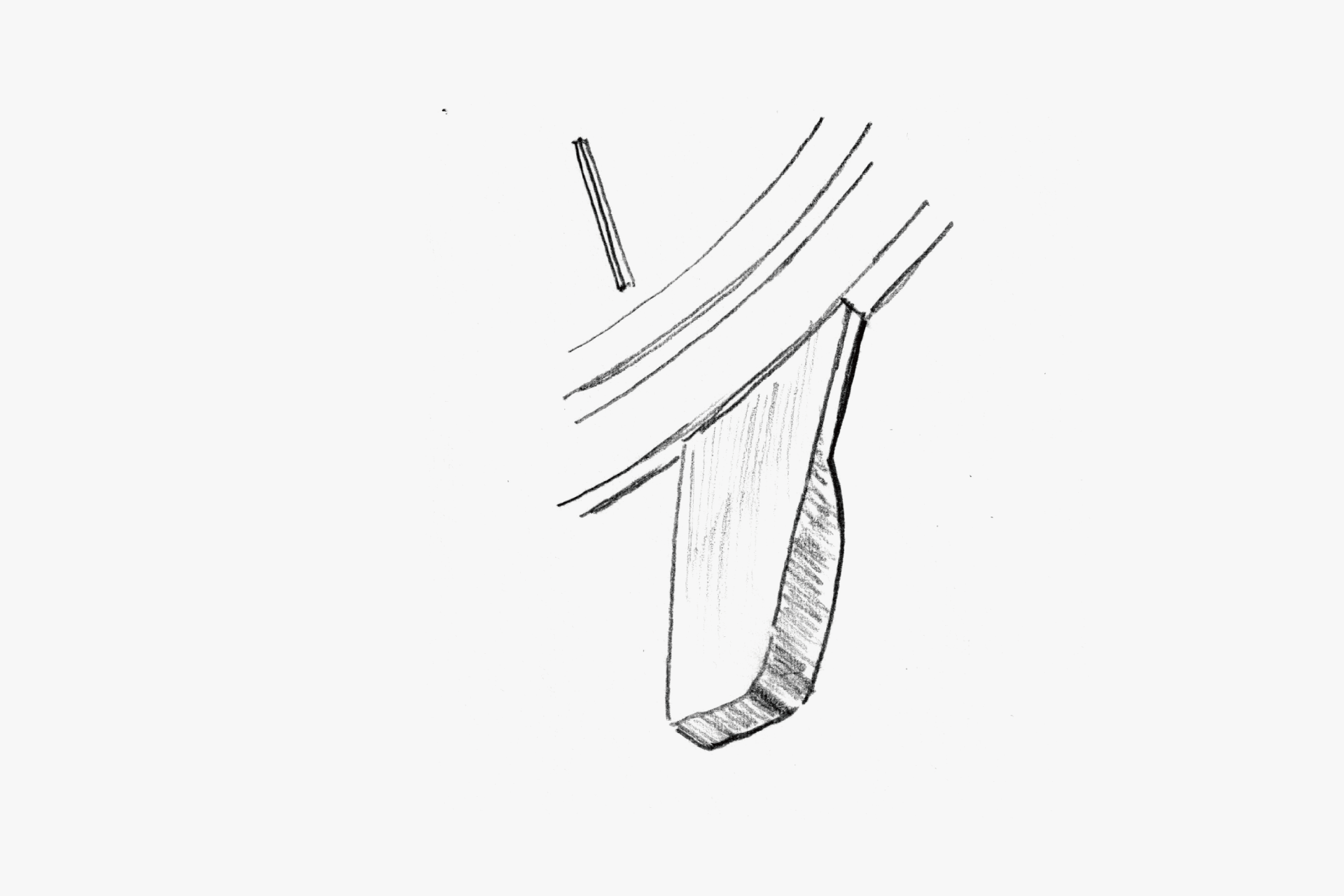

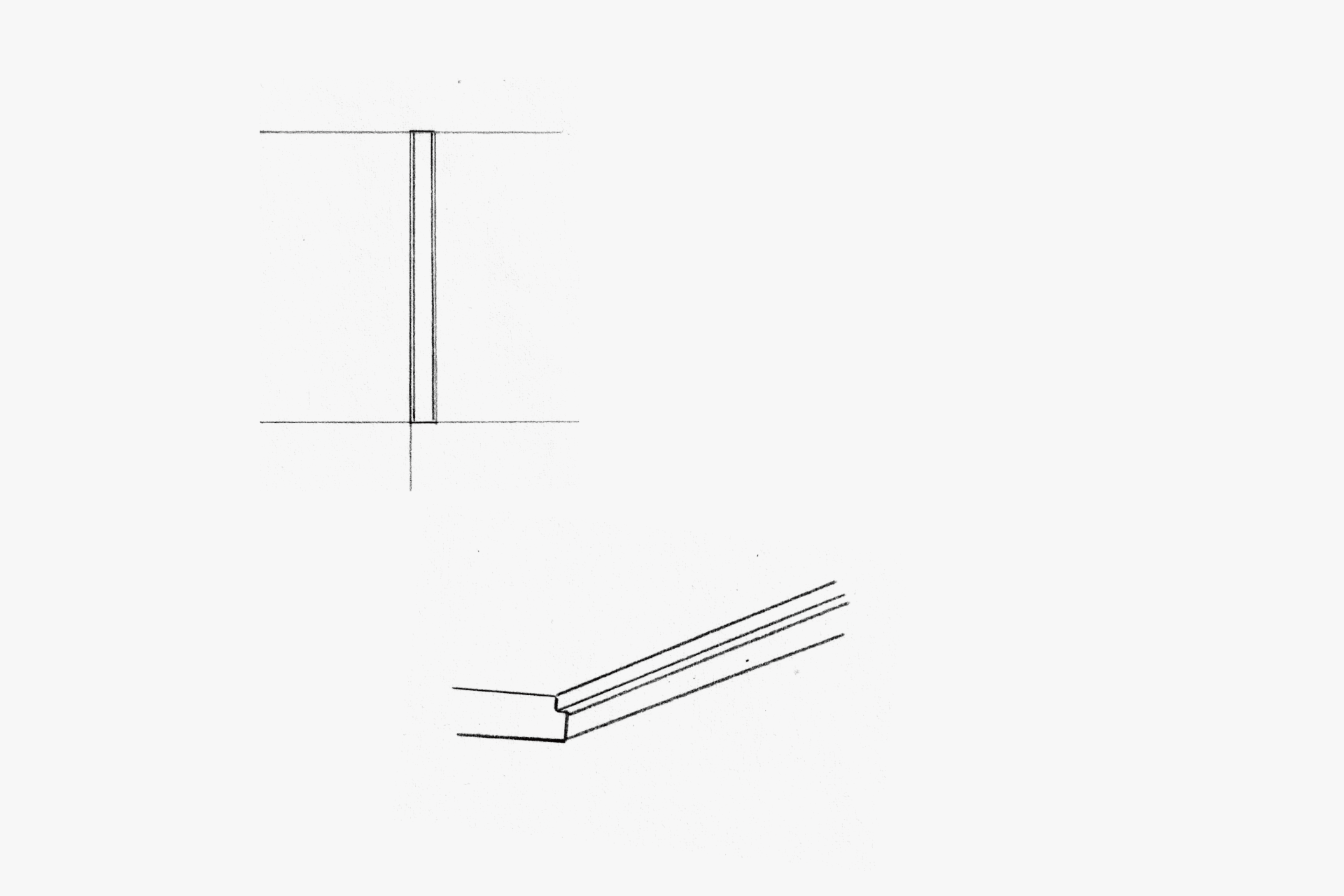

The vertical surfaces of the case are made thinner, creating a visual impression of even greater thinness.

By applying extremely small radius corner treatments to the ridges, the thin flat surfaces and ridges are made to stand out clearly.

The side surface of the case is made thin and tall, further enhancing the visual impression of thinness.

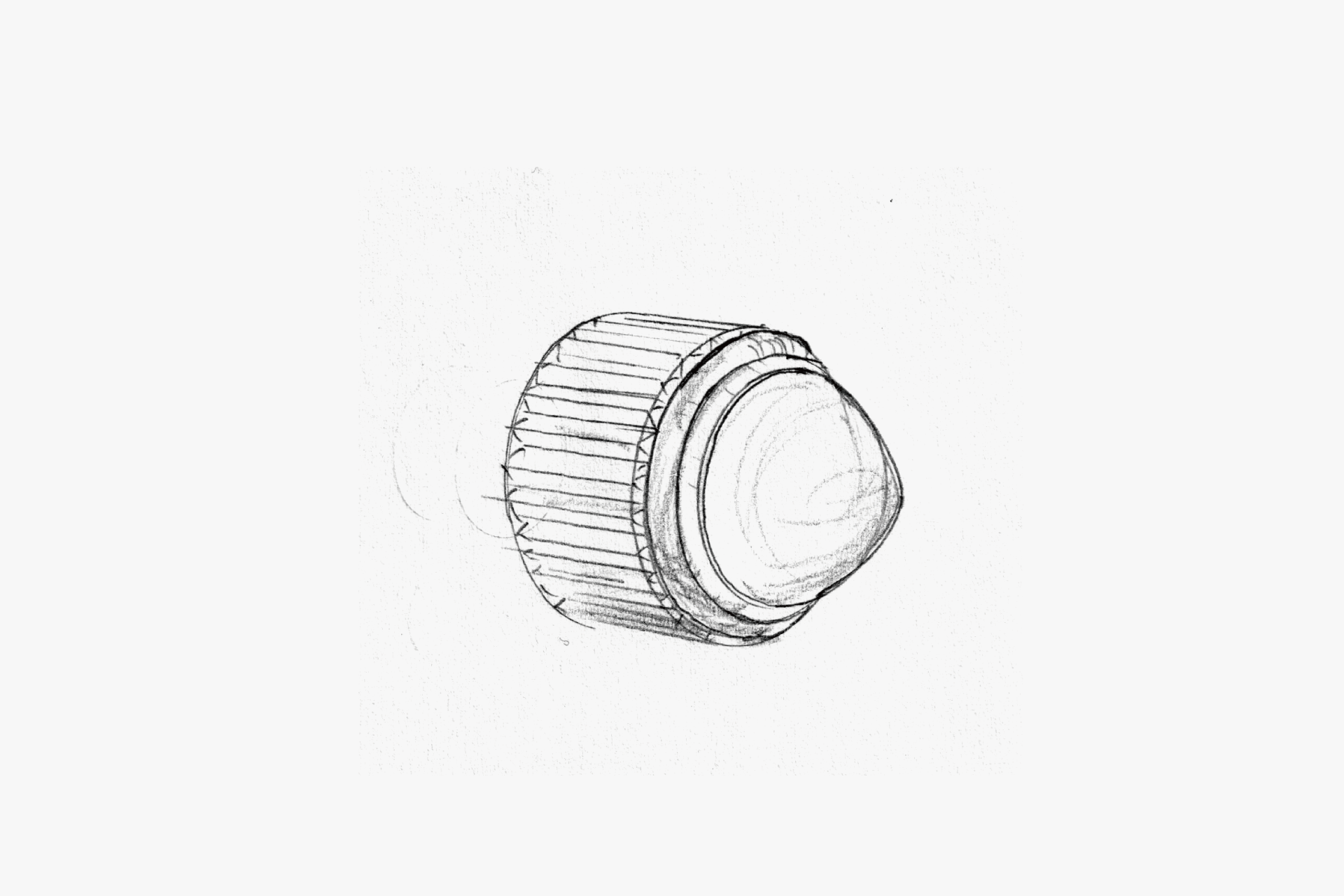

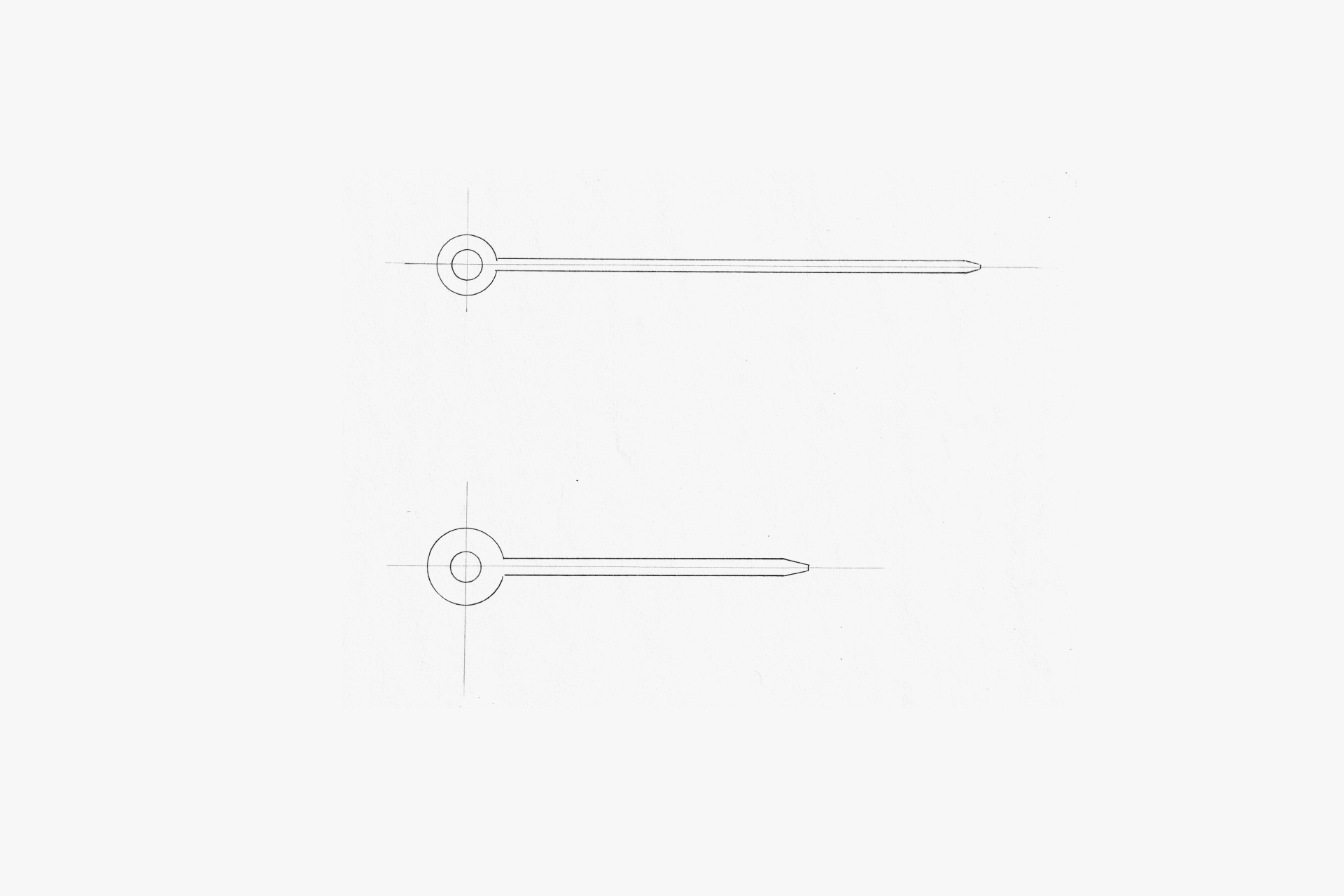

By embedding a stone that tapers to a point into the crown, a slim impression is achieved.

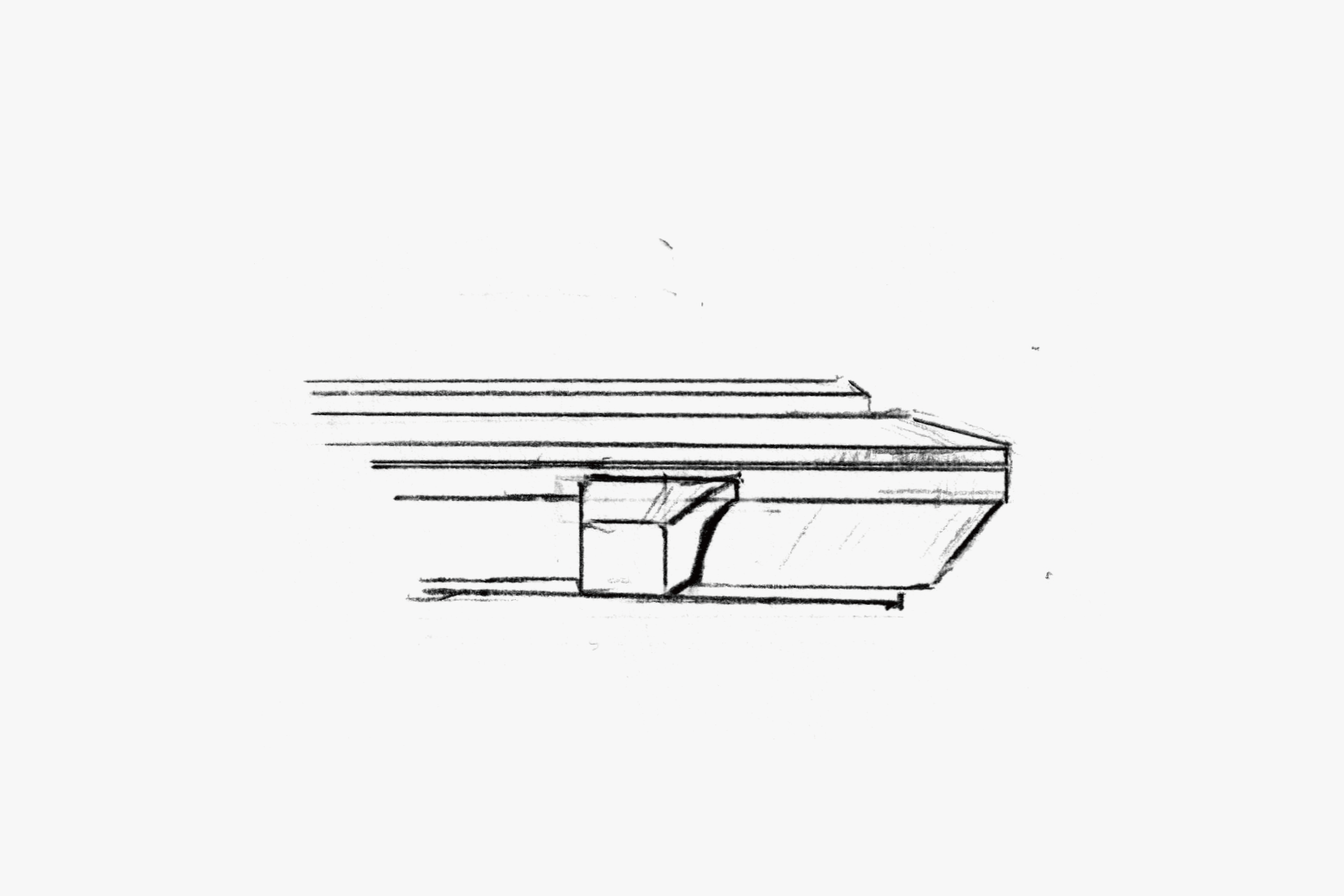

By minimizing the number of ridges forming the exterior, the thinness is further accentuated.

The upper surface of the ultra-thin hands is arc-cut, making the cross-section as thin as possible.

On both sides of the applied index, protruding cuts only several tens of microns wide are made, creating a sense of precision.

ENGINEER'S EYE

The Shockingly Slim Quartz

Aiming for a more essential value—a “high-grade watch,” we planned and developed what was then the thinnest quartz watch in the world.

The development target for the movement was a thickness of “0 mm.” While 0 mm itself was impossible, rather than thinning each component of a conventional movement bit by bit, we pushed to the limit the thickness of the parts indispensable to a quartz watch—gears, motor, and circuit—and advanced development of an ultra-thin movement by stacking them.

The crystal resonator was not the common cylinder type but a specially developed, exceptionally thin 0.9 mm unit. It was mounted on a glass substrate and sealed with a metal cap, and because these were first-time materials and structures for us, production proved extremely difficult. Despite the thinness, by adopting a temperature-compensation capacitor, we achieved high precision of ±10 seconds per month.

The most challenging task of all was developing the motor that drives the hands. Because the motor’s size is proportional to the torque it delivers, we repeatedly conducted carry tests with prototypes that reduced torque, ultimately finding the balance point between size and motor performance and achieving miniaturization.

For the mechanical parts as well, it was not enough to be merely thin; we had to more than double the precision compared to conventional quartz watches for factors such as main plate warpage, gear end play, and the positional accuracy of the axes. Manufacturing was carried out with the utmost care, and selected skilled technicians were assigned to assembly.